We have very little from the Italian opera composers who were Verdi’s contemporaries. While Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti dominated the first half of 19th-century Italy, Verdi alone dominated the second half; his contemporaries, Mercadante, Cagnoni, Ricci, and Pacini, are unheard of among today’s American ticket buyers. This begs the question, what did Verdi have that his contemporaries lacked? Perhaps Verdi’s greatest gift was an inner voice that led him into new territory, into concise and sometimes violent dramatic expression. Verdi was soundly criticized for this in the press and by music professors (as was Rossini), but the opera-going public made him rich (as it did Rossini).

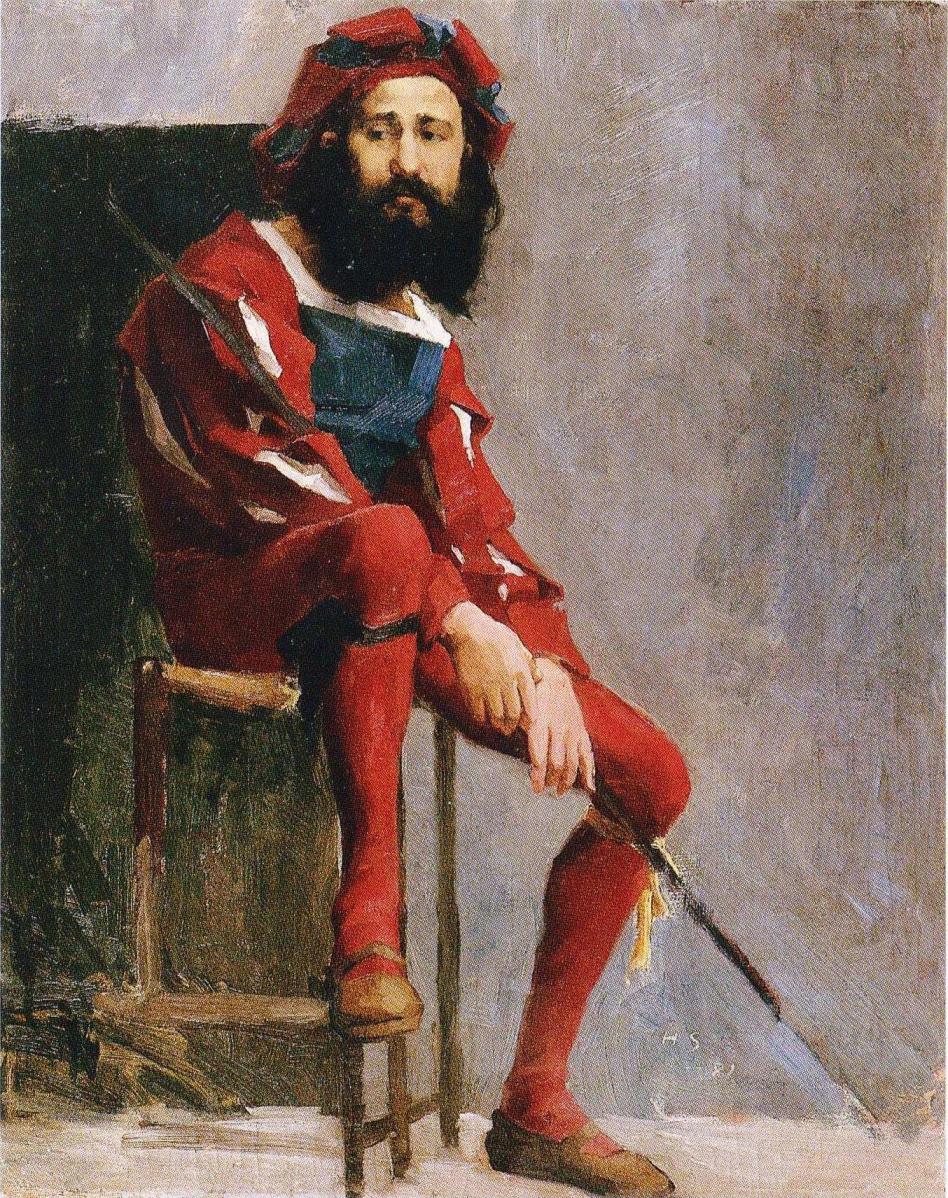

Rigoletto, Helene Schjerfbeckin, 1881

Rossini revitalized Italian music with his great joie de vivre and forward pulse, but more important, he gave Italian opera a course-changing innovation; he reconceived the scene as the basic building block of opera composition, where the aria had served that purpose before. This was an enormous step forward in allowing dramatic development through music. Donizetti refined this innovation, but Verdi took dramatic content in opera to its apogee. It is in Rigoletto that we get the first glimmer of Verdi’s hope to make the act, rather than the scene, the basis for opera composition, unifying the dramatic context even more. In a letter to his Il trovatore librettist, Salvatore Cammarano, Verdi expresses this revolutionary idea,

“If in opera there were neither cavatinas, duets, trios, choruses, finales, etcetera, if the whole work consisted, let’s say, of a single number, I should find that all the more right and proper.”

In an era when each musical number, nearly every canzona, cavatina, aria, chorus, duet, and so on, was musically self-contained and ended with an opportunity for audience response, the idea of fusing all the music in an act into a single musico-dramatic movement, like a movement of a symphony, was revolutionary. Wagner was waging the same war north of the Alps, causing riots in Paris. As Wagner wrote his own libretti, he had an easier time of it. Verdi had to cajole, badger, threaten, and plead with his librettists to tighten up the form, conjoin individual numbers, and think in longer sections. When he lost patience, he simply altered the libretto himself in order to achieve the drama he knew the plot contained and that his music could illumine. We owe Verdi a great deal, not only for the two dozen operas he created through a life of unstinting effort, but for his determination to expand the dramatic capabilities of the art form.

Verdi gave us twenty-six operas (more, if you count the major revisions), and among them are many of the most performed operas in history: Aida, Un ballo in maschera, Don Carlo, Falstaff, La forza del destino, Macbeth, Otello, Rigoletto, La traviata, and Il trovatore. His arias rank among the most effective in the repertoire, and he is never sentimental, never prolix, and almost always concise. He had an unerring ear for the surprising leap and an instinct for brilliant expression in both text and music. No composer is a better dramatist.

Verdi was drawn to characters with duel natures at conflict. You will find this internal strife in many of Verdi’s principal characters: Rigoletto, Otello, Macbeth, Azucena, Eboli, Amenris, even Violetta, and of course, Rigoletto.

The opera Rigoletto was based on the Victor Hugo play, Le roi s’amuse (the king takes his amusement). When Victor Hugo premiered this play in 1832, one suspects hecouldn’t have believed it would find much

Isabella Ivy as Gilda and Matthew Hanscom as Rigoletto

Opera San José, Rigoletto, 2014

of an audience. About the sexual rapaciousness of Francis I, one of the most beloved of all French kings, and perhaps hinting at the behavior of King Louis-Philippe (then in power), it would have been a controversial play at best. As the authorities closed the play after one performance, we will never know if Le roi s’amuse could have succeeded on the French stage at the time; however, the ensuing law suit that Hugo brought against the crown for restricting his freedom of speech (which he lost) made the play famous, and it became a best seller in printed form. Soon, a copy of the script found its way into Verdi’s hands.

What attracted Verdi to Hugo’s play was the character of the court jester, Triboulet, which Verdi thought to be an entirely original stage creature. Renamed Rigoletto, the jester was elevated to the title role, and the opera was relocated to the duchy of Mantua. Verdi fleshed out this court jester and made him as immortal as any character in opera can be. Rigoletto is much more than a tortured soul. Abused from childhood for his physical deformity, he is richly drawn and deeply human, passionate, willing to act, cunning, tortured, self-aware, and loving. He is a man of his time, when the rule of Italian dukedoms could be taken by might, and when assassins offered their services to strangers in dark streets.

Today, most Americans would see personal vengeance at the scale depicted in this opera as an insane extreme, even though we see a lot of it all over the globe. I hope most Americans would view vengeance as yielding only evil fruit, injury begetting injury, a never-ending cycle. This was not the view of Italians in Renaissance Italy, or in many other cultures the world over yet today, where vengeance is ferocious and insatiable. The opera Rigoletto was, perhaps, one of the many influences that reshaped our perception of the dangers inherent in a hunger for violence, for Rigoletto will lose everything he holds dear in his vain attempt to get even.

Melissa Sondhi as Gilda and Edward Graves as The Duke

Rigoletto, 2024

Photo Credit: David Allen Photography

What he loses is his daughter Gilda, the only creature on earth who loves him, and the only thing he loves at all. Gilda has recently come home after a decade of convent training, barely sixteen, totally inexperienced, she is infatuated with a youth she sees at daily mass and who she mistakenly believes is a student. Gilda will ultimately sacrifice her life to save his. Her winning presence, so perfectly drawn in a single duet and one breath-taking aria (she has much more to sing in addition), has placed her among the most cherished of Verdi heroines.

Though she has been in love at a distance for some time, it isn’t Gilda’s innocent love and bravery that keep this opera alive and in performance the world over, it is Rigoletto’s

protective love for his child. Victor Hugo and Verdi understood the desperate power of a father’s love and they have delivered us a masterpiece. I hope you will find it a remarkable experience.